San Francisco more or less created psychedelic rock in the 1960s, although it can be argued that the first song worthy of that tag came from London, where the Yardbirds cooked up “Happenings 10 Years Time Ago.”

San Francisco more or less created psychedelic rock in the 1960s, although it can be argued that the first song worthy of that tag came from London, where the Yardbirds cooked up “Happenings 10 Years Time Ago.”

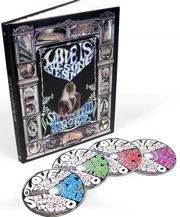

“Love Is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets 1965-1970” tracks the progression of the local sounds starting with bands influenced by the promise of the “Rubber Soul”-era Beatles and running through the golden era of psychedelia.

Rhino’s four-CD set comes in a box-sized package, with the essays and a photo gallery contained in a 120-page book. This is a coffee table CD set, if there ever were one.

There are 77 tracks, more than four hours of music. The audio is outstanding, up to Rhino’s standards in every way.

“Seismic Rumbled” (disc 1) features early contributions from the Warlocks (later the Grateful Dead) to the Great Society (later the Jefferson Airplane) and the Charlatans (Dan Hicks, hairy).

“Suburbia” (disc 2) looks back at the edgy music being created in nearby places like Berkeley and Sausalito — and especially San Jose, which produced the proto-psychedelic hit “Psychotic Reaction” from the Count Five and “Rumors” from the Syndicate of Sound.

“Suburbia” (disc 2) looks back at the edgy music being created in nearby places like Berkeley and Sausalito — and especially San Jose, which produced the proto-psychedelic hit “Psychotic Reaction” from the Count Five and “Rumors” from the Syndicate of Sound.

“Summer of Love” (disc 3) is where you’ll find most of the psychedelic music that had to be in the set: “The Golden Road” (the Grateful Dead), “Omaha” (Moby Grape), “White Rabbit” (Jefferson Airplane), “Soul Sacrifice” (Santana), etc. A preview of heavy metal comes with the sonic attack of Blue Cheer’s “Summertime Blues.”

“The Man Can’t Bust Our Music” (disc 4) looks at some of the more sophisticated offerings from the scene, as acts like the Dead and Airplane buckled down to the business of being music stars. Included are It’s a Beautiful Day’s “White Bird,” the Dead’s eternal jam “Dark Star,” and “Mexico” from the late-period Airplane.

The set was produced by British rock historian Alec Palao, whose many credits include a definitive Creedence box set. He writes in the intro that there was no such thing as a ’60s San Francisco sound. At least not one that “any rote history” would cover.

“What the bands from San Francisco did have,” he writes, “was a fellowship that actively encouraged the active exploration of rock’s outer fringes.”

Ben Fong-Torres, well known to Rolling Stone readers of the era, seconds the sentiment in a short essay.