A screaming comes across the sky. It’s Hyde Park in Central London, July 1969. A largely unknown quartet takes the stage, opening for the mighty Rolling Stones.

As many as a half million rock fans get their first taste of “21st Century Schizoid Man,” the apocalyptic opening number by King Crimson, a local band that grew out of cult psychedelic act Giles, Giles and Fripp.

Psychedelic music, which had held sway over London town for several years, was on the wane. Flower power withered and sounded almost quaint here in the summer of hate. The Vietnam war raged. Cambodia suffered the bombardment of the superpower across the pond. The Manson murders and Altamont waited in the wings.

“21st Century Schizoid Man” brought the shock of the new. Aggressive. Frenetic. Scary. Almost seven minutes of shriek, propelled by frenetic drumming and anguished alto sax. Starts and stops, executed with precision, played by musicians whose chops well exceeded those of the day’s rock elite.

And the lyrics, nonsensical yet impregnated with accusatory anger, delivered by bassist Greg Lake: “Blood racks barbed wire / Politician’s funeral pyre / Innocents raped with napalm fire,” he cried.

“It fired the starting pistol on progressive rock,” the singer would say later.

The 8-month-old King Crimson would go on to perform two more songs from their yet-to-be-recorded debut album: the dreamy “Epitaph” and the crashing “The Court of the Crimson King.”

The Hyde Park unveiling deemed a success, the band entered Wessex Studios on July 21, just as Neil Armstrong took his first steps on the moon. The resulting album — “In the Court of the Crimson King” — proved seminal, a giant leap for prog, the new rock genre that had been bubbling up from the underground for at least a year.

Psychedelic rock and prog would coexist uneasily for a few years — proffered by bands such as Yes and the Moody Blues — but few who heard the “Crimson King” album would confuse it with “Sgt. Pepper” or “Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake.” This was chilly and pensive music for a new decade. Cold-blooded and sexless, a cynic might say.

Virtually nothing born of 1960s rock of came without antecedents, of course. By the time King Crimson entered the studio, they’d no doubt absorbed the Moody Blues’ current psychedelic-symphonic “On the Threshold of a Dream,” as well as its two lush LP predecessors. The Jimi Hendrix Experience had just called it quits after three years of psychedelic sounds grounded by the precise and jazz-influenced drumming of Mitch Mitchell. And of course the King Crimson album’s key instrument, the electronic mellotron, had been in use for a few years, notably with the Moody Blues, the Beatles, Bee Gees and Stones.

No doubt the gentlemen of King Crimson ventured farther afield for their influences. Consider what might be glimpsed behind the curtain of the album’s 12-minute psychedelic chill-out “Moonchild”:

Electronic music had resurfaced from the avant-garde in the late ’60s with Moog synthesizer releases such as “The Nonesuch Guide to Electronic Music” from Beaver & Krause and Walter Carlos’ “Switched-On Bach.” Fifty Foot Hose’s debut album of a few years earlier was known to aficionados of the underground, melding the psychedelic and the electronic. “Revolution 9.” White Noise’s “An Electric Storm” escaped earlier that summer of 1969. Frank Zappa’s “Uncle Meat” attacked the market a few months before.

Listen for the ghosts of Miles Davis’ “In a Silent Way” and the angular art of Ornette Coleman. King Crimson’s guitarist Robert Fripp and polyrhythmic drummer Michael Giles especially attuned to American jazz. (“Let’s face it, Miles was progressive,” Fripp has said.)

What was notably missing in this fledgling prog of King Crimson were the R&B and blues foundations of British rock. “In the Court of the Crimson King” displays virtually none of the mainstream African American influences heard in almost all UK and U.S. pop acts of the time. That distinction would become a tell-tale of progressive rock for decades to come.

Yet “In the Court of the Crimson King” (subtitled “An Observation By King Crimson”) remains the touchstone for all prog rock to come because of its startling originality — a relentless cohesiveness and clarity of vision. A long-playing album of just five songs, with no apparent commercial aspirations (or at least accommodations). Longhair music for longhairs. “An uncanny masterpiece,” in words of young Pete Townshend.

“21st Century Schizoid Man,” the opening track, was the final song recorded for the album. Lyricist Peter Sinfield said his words were “angry, against the Vietnam war — an angry, modern song of its time.” (Sinfield was a former bandmate of Ian McDonald who was primarily a poet. He is credited with coming up with the name King Crimson and was considered a band member.)

Greg Lake’s vocals are in-the-red distorted, adding to the song’s vibe of angst and anarchy. The opening riff — played by Ian McDonald on B-movie sax and Robert Fripp on guitar — anticipates heavy metal and provides the foundation for what seems a quicksilver musical scheme. The big-band-influenced middle instrumental section is subtitled “Mirrors.” Fripp’s snarling solo ventures into atonality, and the concluding section flirts with free jazz. “It was so hard to play, and it was so terrifying,” Fripp said a few years later.

Running 7 minutes 20 seconds, “Schizoid Man” is arguably the hardest-rocking numbered ever performed by King Crimson. It remains the band’s signature song and provides a crowd-pleasing concert climax to this day. Despite the track’s wild popularity, the band quickly strayed from the template, with the (glaring) exception of “Pictures of a City” on the second album. The song inspired dozens of covers by name bands, and was even sampled by Kanye West for “Power.” (In 2019, Rolling Stone felt compelled to write its history in a two-part article calling it “Prog’s Big Bang.”)

“I Talk to the Wind” was a McDonald holdover from Giles, Giles and Fripp. (One early attempt at the track featured singer Judy Dyble of Fairport Convention.) After the savagery of “Schizoid Man,” the ballad offers a soothing tonic. Pastoral and tilting toward psych-folk, a popular subgenre of the place and time. McDonald shares vocals with Greg Lake, but it’s undoubtedly McDonald’s show. His flute playing evokes the classical, and guides the listener. Sinfield’s lyrics are vintage hippie fare — “Said the straight man to the late man / “Where have you been?” / I’ve been here and I’ve been there / And I’ve been in between” — with a dash of late ’60s disillusionment: “I talk to the wind / My words are all carried away / I talk to the wind / The wind does not hear, the wind cannot hear.”

“Epitaph” returns the listener to the badlands of the opening track, riding in on a timpani roll and destined for a place where “silence drowns the screams.” Cinematic and drenched with mellotron, the midtempo song’s genesis was a pre-existing poem by Sinfield. Despite the existential gloom, it brings to mind the Moody Blues. The music is credited to all band members, who reportedly struggled for 10 hours to get it on tape (compared with the one-take “Schizoid Man”). A cold-war nightmare, the narrator fears the handiwork of “fools” with their “instruments of death.” “Confusion will be my epitaph,” he concludes. Includes amorphous sections titled “March for No Reason” and “Tomorrow and Tomorrow.”

“Moonchild” is the “Revolution 9” of “In the Court of the Crimson King.” It begins as a straightforward ballad sung by Lake and typical of the psychedelic era, dubbed “The Illusion.” From there, Fripp, Giles and McDonald graft on an improvised 10-minute section, “The Illusion.” It’s unusually melodic, in retrospect, one of the era’s best flirtations with electronic music and Sun Ra-inspired space rock. The song, in fact noodling filler born of necessity, takes up the majority of side 2. In its original version, Fripp swans in with quotes from “The Surrey With the Fringe on Top,” a vamp sometimes repeated in concert.

“The Court of the Crimson King”: Where is our king? We hear of the black queen, the juggler, the piper, the keeper of the city keys, even the fire witch. Yet no word of the monarch. Such is the mysterious tale of the “Crimson King,” one of the bookend triumphs of King Crimson’s debut album. Full of sweep and spectacle, the song appears to dwell in the halls of a British monarch with a particularly bloody reign (apparently the definition of a “crimson king”). Again, the music comes from McDonald and the lyrics from Sinfield. The rock poet hits his peak here: Compare these black-death lines with, say, the collegiate existentialism of “Epitaph.”

“Crimson King” remains one of the most famous songs to be dominated by the mellotron, along with “Strawberry Fields Forever.” Music students of the day may have felt a tinge of recognition: The melody was lifted from Samuel Barber’s “Essay for Orchestra” (1938). This dense, humid work owing its origins to “a sort of Bob Dylan song,” Sinfield says. The number runs 9 and a half minutes, split into four sections. Its natural state seems a troubadour’s tale, told with flute and acoustic guitar. Yet upon every mention of the monarch, a symphonic assault keyed by a drum roll, full-on instrumentation and men’s chorus. King Crimson ends its epic song with crashing repetitions of the titular riff, followed by a breathless electronic eulogy.

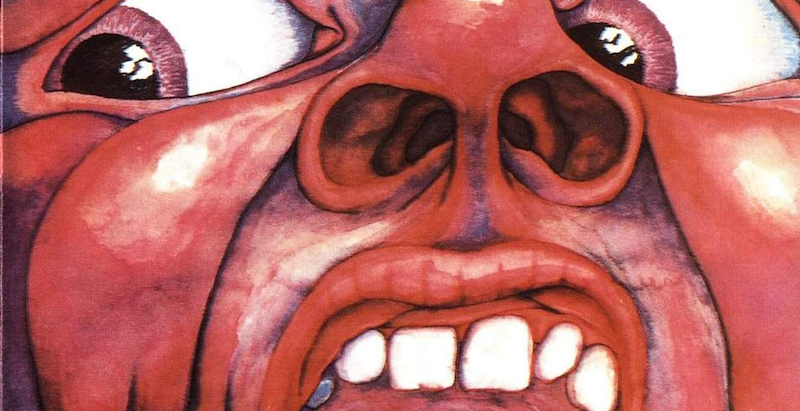

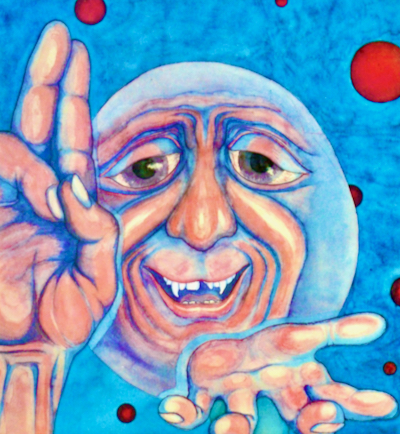

Some of the credit for the initial success of “In the Court of the Crimson King” must go to artist and roadie Barry Godber, who drew the startling Schizoid Man. The watercolor cover artwork appeared on the sleeve without any mention of the band’s name, a daring move by an unknown act.

“Crimson King” has remained relentlessly in print over the past half century, accommodating the new generations of fans drawn to its modern sounds. Discogs lists more than 330 versions. In 2019, audio wizard Steven Wilson remixed the album into 5.1 surround and stereo versions for an anniversary box set. Other significant reissues came in 1982 (Mobile Fidelity) and 2009 (Wilson).

Excellent review on “In The Court of The Crimson King.” Thank you so much, it made me appreciate it all over again. I bought this album back in 1969, at American Records in Torrance, CA, down the street from El Camino College. I’ve been a fan ever since. I’ve seen King Crimson at least 20 times or more, including 1 of 3 nights at the Royal Albert Hall, 50th anniversary in 2019. Stay safe.

ultimate prog with fabulous psychedelic moments (Moonchild <3)

Not many (any?) debut albums as staggering as this one.

OMG I heard this playing in a record shop sometime in the early 70s and even though I haven’t heard it since I remember it almost note for note. The way music triggers memory is awesome!

I have my copy on vinyl and it’s one of my favourite treasures!

Saw the original lineup, on a reunion tour of this album, a few years ago. Still fantastic.

There needs to be more love for “I Talk to the Wind.”

Saw them in the 70s at Birmingham town hall – still have the album. Apparently if it’s got the right Island label on its worth a bit!

Fabulous … saw KC at a free concert in Hyde Park early 70s …. brilliant

It was exciting to be a teen and listen to ‘Epitaph’ on our full bass £50 stereo systems back in the day. The ponderous rhythm, the mellotron and the profound lyrics made me certain we were part of a tumultuous era. Then glitter rock came along and I thought, ‘Oops!’

Was way ahead of it’s time, even when pushing the boundaries was becoming the norm. One of my favourites…

One of the best ever bands I saw in the seventies at Birmingham Town Hall.

Los primeros albunes de los Crimson son increibles