“This is acid music,” said Carlos Santana, who should know.

Santana was praising the dark and adventurous music found on Miles Davis’ 1970 album “Bitches Brew,” but he could have been referring to the genre-busting sounds made by the trumpeter’s groups between, say, 1969 and 1976.

“Bitches Brew” was by far the most famous and successful of the albums Davis made during this first “electric” period, but the double LP set serves here as a poster child for his recordings of the time. “Brew” has been called “the aural Mount Rushmore of jazz fusion.”

While Davis’ mid-1970s bands were a bit short on star power compared with the “Brew” crew, the live recordings “Agharta” and “Pangaea” (the so-called Twins) and “Dark Magus” reflect perhaps the pinnacle of this music. Of course, albums such as “In a Silent Way,” “Jack Johnson” and “Live-Evil” have much to offer the adventurous listener.

“You can hear that anger and darkness and the craziness of everything that was still in the air from the ’60s when this music was made,” says the guitarist Santana, a Fillmore Auditorium regular and witness to the eruption of the electric Miles Davis.

Davis’ head-music period began, more or less, when “Bitches Brew” was recorded in August 1969. He’d been absorbing psychedelic soundscapes, acid rock and the aggressive, artful new funk of James Brown’s band: “The music I was really listening to in 1968 was James Brown, the great guitar player Jimi Hendrix, and a new group Sly and the Family Stone,” Davis wrote in his autobiography.

When Dylan went electric, he plugged in. When Davis went electric, he stuck his finger in the socket.

Even the most dedicated Davis fans who’d been along for the ride with the albums “Filles de Kilimanjaro” and “In a Silent Way” were in for a shock. When Dylan went electric, he plugged in. When Davis went electric, he stuck his finger in the socket. The jazz star was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for good reason.

The music had “that snapping fire that you sense when you go out there from the spaceship where nobody has been before,” wrote the critic Ralph J. Gleason.

There was, not surprisingly, some push-back to the jazz master’s excursion into head music. “Miles wants to be Jimi Hendrix,” Cream’s Jack Bruce said, “but he can’t work it out on trumpet.” Davis fired back: “All the white groups have got a lot of hair and funny clothes — they got to have on that shit to get it across. … White groups don’t reach me.”

That sentiment didn’t extend to Davis’ “Bitches Brew” support. Among the players were Chick Corea, the Englishmen John McLaughlin and Dave Holland, the Austrian Joe Zawinul as well as blues-rock veteran Harvey Brooks — all white. (I once asked Wayne Shorter, who was featured on the album, about charges that Davis was a racist. He shook his head and noted that Davis took a lot of crap from “the brothers” for working with McLaughlin, but wouldn’t hear it. Davis even titled one song on “Brew” after the fiery guitarist.)

Davis had long depended on support from white audiences, but in the mid-1960s his commercial appeal had faded somewhat. Album sales were well off and some club dates saw half-empty houses. He’d recorded for almost a decade for the major label Columbia, whose boss, Clive Davis, pushed for Davis to explore opportunities in the underground music scene.

Davis and his sextet then played Bill Graham’s Fillmore East in New York City, teamed with rockers Neil Young and Steve Miller. The eclectic booking wasn’t that unusual for Graham, who liked to mix up genres, and had hosted Charles Lloyd, Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Cecil Taylor at his Fillmore West.

The next month, Davis’ sextet debuted at the Fillmore West, sharing the bill with the Grateful Dead. (He would return to the venue several times.) Three months after the March 1970 release of “Bitches Brew” — June 17-20 — Davis and band again played the Fillmore East. Davis then toured with Santana and was featured at the Isle of Wight pop festival in England. Some of this challenging live music was released at the time, and most of it has surfaced in repolished form, notably on “Black Beauty” and “Miles at the Fillmore — Miles Davis 1970: The Bootleg Series Vol. 3.”

Davis’ music of the time is generally referred to as jazz fusion, but that’s only part of the story.

Along with the fuzz, warp and froth taken from the psychedelic music of the late 1960s were elements from hard bop and world music. Drones and sitars. Space rock.

“You can hear the template for hip-hop, house, drum and bass, electronica. … Miles was doing all of that in the early 1970s,” said the Harlem-based critic Greg Tate.

“Bitches Brew” gave Davis his first gold record. Yet the new music proved most commercially successful with Davis’ sidemen who went on to their own fusion outfits. Weather Report (Shorter and Zawinul), Return to Forever (Corea), the Mahavishu Orchestra (McLaughlin) and Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters. These bands made bold music and sold lots of records, but were more genre-bound to what we’ve come to know as fusion than Davis’ more eclectic electric explorations.

“Bitches Brew” begins with a Frankenstein of a song, “Pharaoh’s Dance.” Producer Ted Macero made something like 20 edits to create the track (a musique concrète technique he would employ to make sense out of chaos throughout Davis’ electric period). The sidelong composition was credited to Zawinul, the keyboardist who was the co-creative force on “In a Silent Way.” As with all of the tracks on “Brew,” it is largely a product of in-studio improvisation on a theme. At times “Dance” sounds like a keyboard battle between Weather Report and Return to Forever. There were three players on keys: Zawinul (left in the mix), Corea (right) and Larry Young (center).

“Bitches Brew” was the first track recorded in the three-day sessions. It contains more than a dozen edits/loops. It’s a dark and strange work, the longest on the album. Davis’ playing is especially strong and up front. Listen for McLaughlin’s solo about the 8-minute mark, giving the band a second wind. It’s especially cinematic and brings to mind Herbie Hancock’s soundtrack for “Death Wish” that came five years later.

“Miles Runs the Voodoo Down,” probably the most famous of the album’s songs, gets its heartbeat from conga player Don Alias, who moved over to the drum kit. The percussionist said he got the beat while taking in Mardi Gras. The bedrock bass line drives the piece, however. It contains some of Davis’ best playing on the album. Like the title track, “Voodoo” was a staple of Davis’ live performances for several years. The title reportedly was a nod to Jimi Hendrix.

That’s the big three, but there are pleasures to be found in “Spanish Key” and “Sanctuary,” both calling back to previous Davis works. “John McLaughlin” was a byproduct of the day 1 “Bitches Brew” session and clocks in at a restrained 4:22. Davis does not play on that track.

Seekers of the strange should be sure to check out “Feio,” the psychedelic Shorter composition that’s included as a bonus track on some releases as well as streaming versions of the album. It’s an ambient adventure featuring Airto Moreira on the curious instrument curica and compelling electric bass from Dave Holland. (It was recorded five months later.)

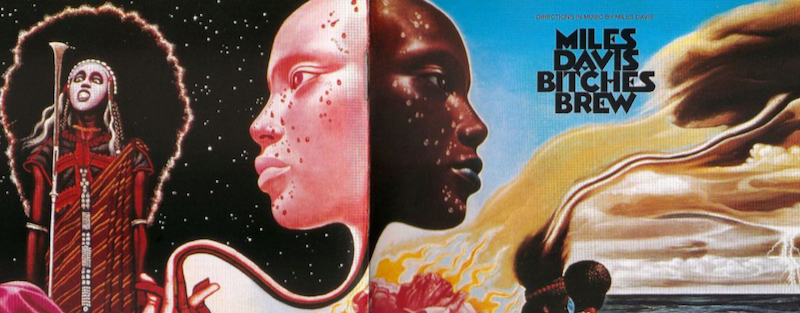

Liner notes: “Bitches Brew” was famed for its colorful yet mysterious cover artwork, done by the French surrealist Malti Klarwein. The artist’s work also appeared on the cover of “Live-Evil” and Santana’s “Abraxas,” among many others. … The album’s arresting title was never clearly explained, although a leading theory is it refers to a group of women who influenced Davis’ aesthetic at the time. The “Bitches” also could refer to the musicians, a hipster compliment. The “Brew” is in the grooves, of course. “The title fit the music; the cover fit the music,” producer Macero said.

Buy “Bitches Brew” on Amazon (vinyl)

Buy “Miles at the Fillmore” on Amazon (CD)

Buy “Black Beauty” on Amazon (CD)

Excellent analysis of this landmark album. I bought it the year it came out. I was so lucky to come of age during that spectacular time in music history. Love your newsletter.