“I want to be able to smell the sawdust,” John Lennon demanded. “I want to taste the circus.”

What John Lennon wanted in 1967, he got. And so the production team of George Martin and Geoff Emerick went to work, weaving a crazy-quilt backing for the song Lennon titled “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!”

The Abbey Road duo were no strangers to the set of studio tricks employed in the psychedelic era. For Lennon’s “Tomorrow Never Knows,” they’d employed musique concrète techniques such as tape fragmentation and looping, as well as reversed instrumentation.

Martin talked Emerick into cutting circus instrument sounds into fragments, then distributing them by tossing them in the air. Patched together, they formed a surreal but somewhat coherent backdrop for Lennon’s big-top spectacular. The studio trickery had just begun, as “Mr. Kite” remains one of the most complex on the album and in the Beatles catalog.

The resulting track, although less than 3 minutes, held down a cornerstone position on the Beatles’ remarkable 1967 album, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” The track closed out side 1, providing a timely burst of crazy energy and slingshoting listeners onto side 2.

The Fabs’ embrace of flower power and trippy-dopey imagery was in full bloom in the summer of 1967, when the multicolored “Sgt. Pepper” tumbled onto the world stage. Yet the English music-hall influence on “Sgt. Pepper” is as strong if not stronger than the call of psychedelia. Nostalgia had a strong pull in the troubled late 1960s. A Victorian circus fit the bill.

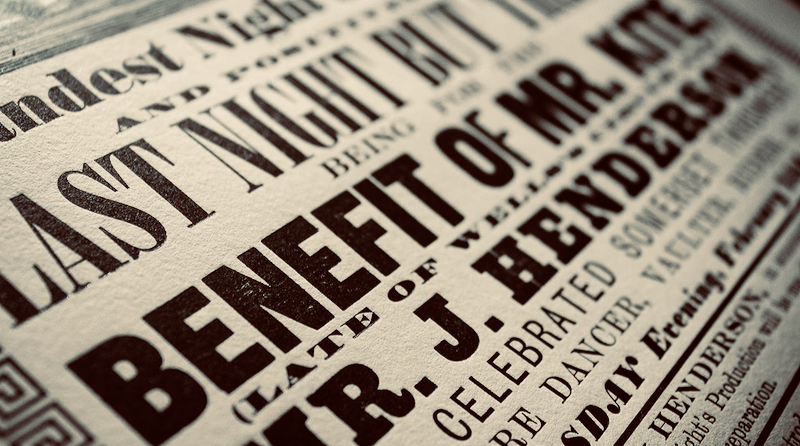

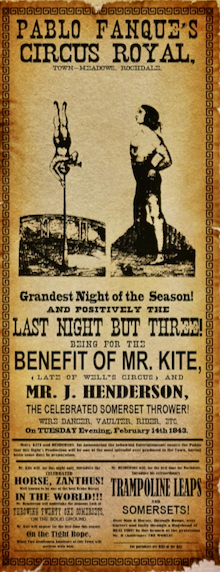

Lennon’s writing continued to look inward in 1967, but he turned at times to newspapers, magazines and other media for inspiration — most famously on the album’s stunning closer, “A Day in the Life.” His road to “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” began with a circus advertisement found in an antique shop and purchased for next to nothing.

Lennon called the songwriting “a straight lift” from that Victorian poster, at that point hanging on his wall near the piano. No need to invent characters.

Let’s meet the cast, a real-life posse from the 1840s:

- Mr. Kite was William Kite, son of a circus owner and a seasoned performer. He’s the chap seen on the poster, balancing head-down on a long pole whilst playing a trumpet.

- The Hendersons were John and his wife, Agnes, known for their skills dancing on wires, trick-riding horses and clowning.

- Pablo Fanque was a black circus owner and a skilled performer of tricks and athletic feats. He had just started his circus. He taught horses to “waltz.”

- And (of course) Henry the Horse … actually named Zanthus on the poster, but Lennon needed the rhyme.

Lennon took a few other artistic liberties with the poster (the Circus Royal became a fair and was moved from Manchester to east London; Mr. H was the one challenging the world), but there’s no doubt the source poster’s clever and antiquated wordplay appealed to the author of “A Spaniard in the Works.” (A “hogshead of real fire” was something like a dumpster fire.) Lennon’s performance as the show’s advance man, complete with theatrical-style patter, could be plopped down in the middle of most Gilbert & Sullivan pieces.

The in-studio evolution of “Mr. Kite” is more interesting than most, and can be tracked via unfinished versions on two official Beatles CD releases: “Anthology 2” and the 2017 “super deluxe edition” of “Sgt. Pepper.” Giles Martin also remixed the song for the latter project. Plus, there’s Giles’ other remix, on the Cirque du Soleil “Love” soundtrack, complete with its mind-blowing quantum leap into “I Want You (She’s So Heavy).”

The Martin-Emerick tape-fragment Frankenstein provides most of the circus swirl, in the song’s waltz section and the closing section, but there’s lots more going on. Lennon and Martin recorded organ runs at half speed; Martin played a glockenspiel and harmonium after attempts to find an old steam organ failed; bass harmonicas played by various Beatles and crew find a home in the center; Paul McCartney chips in some lead guitar.

All this surrealism needs some foundation, of course, and McCartney provides it with one of his remarkable bass performances. Ringo Starr offers crashing cymbals and a satisfying big-top thump.

The solo-years John Lennon was a persistent yet inconsistent critic of his own work — and that of the Fabs. Of “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!” he later said, “I was just going through the motions because we needed a new song.”

Just before his death, though, Lennon had become another gobsmacked fan: “It’s so cosmically beautiful. The song is pure, like a painting, a pure watercolor.”

Mr. Kite!

Henderson? I don’t know!

I still sing that one to myself while I’m making my morning coffee at work. Six o’ clock in the morning and I’m standing there with a quizzical feeling trying to remember who it is that dives through a hogshead of real fire! Thanks, as usual.

Lastly through a hogshead of real fire!