“There’s a fog upon L.A.,” George Harrison intoned, checking in from the intersection of Raymond Chandler and Samuel Beckett.

Or, literally, from on high in the so-called Bird Streets, west of Laurel Canyon and east of Coldwater Canyon.

The line opened the Beatles song “Blue Jay Way,” the product of Harrison’s weary wait at an L.A. rental house, jet-lagged and fighting to stay awake for the arrival of a expat pal.

Harrison flew solo from his bandmates on this summer 1967 trip to the U.S. More than his fellow Fabs, he knew his way around the real U.S. — not just the Chuck Berry-inspired fantasy land that fired up the foursome as youths. Or the hotels-limos-airports screech of the Beatles’ North American tours. (L.A. scenester Kim Fowley called Harrison “the most American of all the Beatles.”)

Harrison was in town to visit friends, including his sitar guru, Ravi Shankar, who had just opened an Indian-music school in the city and was about to play the Hollywood Bowl. After L.A., the Beatle was off to explore the wonders of Haight-Ashbury in that summer of love (a huge disappointment to the ultra-famous tourist as it turned out).

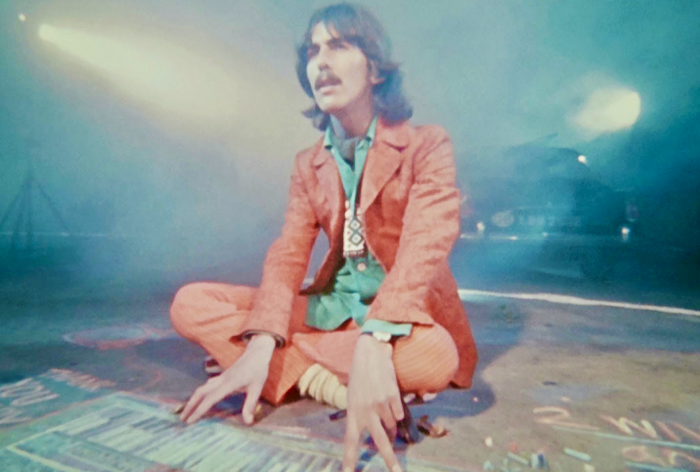

That summer night in L.A., former group publicist Derek Taylor tried to wend his way through the heavy fog and the maze that is the Hollywood Hills. Harrison sat at the rental house’s Hammond S-6 organ and began composing what would be his lone contribution to “Magical Mystery Tour.” The story goes that the song was pretty much done by the time Taylor found his way to Blue Jay. Harrison later said he wrote it “just as a joke to pass the time.”

A little more than a month later, the Beatles began work on Harrison’s latest song inspired by the classical music of India.

“Blue Jay Way” was the successor to “Love You Too” (from “Revolver”) and “Within You Without You” (“Sgt. Pepper”), but unlike those numbers evoked the Hindustani vibe without the use of Indian instruments (or players). (“The Inner Light,” a B-side, would come along in early 1968, wrapping Harrison’s Indian-influenced contributions to the Beatles’ catalog.)

“Love You To” had minimal participation by Harrison’s bandmates, and “Within You” had none. But with “Blue Jay Way,” you get all four Beatles, in the multicolored bloom of their late psychedelic period.

“There’s joy in repetition,” the Minneapolis sage observed, many years later. Indeed, the Beatles seasoned their music with undertones of the Eastern drone technique throughout their psychedelic years. From the startling “Paperback Writer”/”Rain” single to “Love You To” to “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

“Blue Jay Way,” too, had limited harmonic movement, vamping around the root of C. Harrison was not a keyboard player at that point with the simplicity perhaps born of necessity. There is no guitar on the track. The lead such as it is is played by a cellist (Peter Willison, a hired hand who lived near Abbey Road Studios.).

The rhythm track was recorded in one take, in the early hours of Sept. 7, 1967. (The group mostly was occupied at the time with John Lennon’s crazy-quilt construction “I Am the Walrus.”) On this bit of tape can be found one of Ringo Starr’s great performances, the drummer time-traveling — plodding or swinging — as Harrison’s borderline bizarre song demanded.

Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick later wrote that he found the half-baked song “a dirge” and was relieved when Peter Vince sat in for him in the late hours. “Oh, it wasn’t that bad,” Vince reported back to Emerick as a new recording session dawned. Before it was over, a street gang of Abbey Road dial-twisters would get in on the act: The magic of “Blue Jay Way” came in the overdubs.

While the song remained simple, the studio techniques were not. The Beatles opened their bag of psychedelic tricks for “Blue Jay Way,” employing reversed tapes, flanging/artificial double tracking, phasing, speed variations, backward vocals and the Hammond organ’s rotating speaker effect.

Harrison’s lead vocal and the background vocals swanned in by Paul McCartney and Lennon were drenched in the early flanging technique of artificial double tracking (ADT). “Please don’t be long,” the Beatles sang over and over. “Please don’t you be very long.”

A premature mono version was delivered a week later to the makers of the “Magical Mystery Tour” telefilm, finding its way onto that soundtrack. Recording continued, however, with the addition of the cello, also worked over by the ADT. (The instrument’s prominence in the song led to the presence of a white cello abused by the band in the music video, below.) New mono mixes were created. Producer George Martin ran a backward version of the song over a final stereo mix, filling in some parts that hadn’t been properly psychedelicized. (This late addition didn’t make it onto final mono versions.)

The song ends with distorted repetitions of the “don’t be long” bit, swirling into “don’t belong.” The bit of wordplay has been interpreted as everything from Harrison’s complaint about McCartney’s bossiness to a call for the world’s youth to tune in and drop out.

In England, “Blue Jay Way” appeared as side 4 of the “Magical Mystery Tour” double-disc EP, a fitting finale.

In the U.S., the track came in midway through side 1 of the LP. The placement almost a throwaway, as Harrison’s number was sandwiched between the listless instrumental “Flying” and McCartney’s nostalgic jingle “Your Mother Should Know.” Shoddy treatment for one of the few songs used in the “Magical Mystery Tour” telefilm that actually delivered magic and mystery.

For a relatively obscure Beatles number, though, “Blue Jay Way” has enjoyed a savory afterlife. Generations of psychedelic music fans drawn to the ennui-drenched creepiness. A deep track, unsoiled by repetition on classic radio. Music scholars continue to break down its oddball structure and meters (Octovian? Lydian? Ranjani?). As a kaleidoscope of late ’60s studio techniques, it can’t be topped.

Perhaps, though, the story of Harrison and his lonely L.A. vigil continues to resonate and please as a rare private moment that somehow slipped through the wonderwall of Beatlemania.

I always preferred Magical Mystery Tour over Sargent Pepper’s. The later struck me as too popish, while Mystery Tour hit the psychedelic nerves in my head. I only wish the film would have been animated by the same artist who did Yellow Submarine, instead of the boring film that proved The Beatles could do something wrong.

Putting the blame in sharper focus, l’d say the MMT movie proved that McCartney could do wrong, as the other three all had an extra toke & just went along with what was essentially his idea.

Magical Mystery Tour is a pretty awful movie, but the music portions are all pretty good. I love the Blue Jay Way sequence.

My first acid trip was listening to Revolver and I actually preferred revolver as their psychedelic break-out album. But they nailed it with Sergeant Pepper’s. Then Magical Mystery went too far over the top with all its special effects.

Not one of his best imho

He was waiting for Derek Taylor to arrive. George was and is just great; I loved his spirituality as well as his inspired musicianship

Bloody brilliant song