“I’ve led kind of an unusual life,” says Bob Weir, in a moment of understatement.

“I’ve seen stuff that no one has seen,” the guitarist adds, bringing to mind that “Blade Runner” replicant in the rain.

And yes, Weir says, quoting himself: “It’s been a long strange trip.”

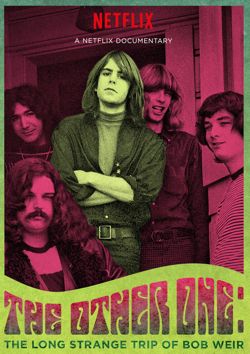

The rhythm guitarist for the Grateful Dead steps out of the long shadow of Jerry Garcia in the documentary “The Other One,” which just made its public debut streaming on Netflix.

The film, by Mike Fleiss, offers a splendid collection of clips, some fine musical performances by Weir and recent collaborators, and of course a snoutful of nostalgia for Grateful Dead fans. It’s an entertaining, fast-moving film whose revelations will be revelations only to non-fans.

The documentary likes to stay in motion:

Weir, who collaborated with the filmmakers, takes visitors along for visits to the location of old music shop where he first hooked up with Garcia; to the site of his boyhood home; and to the infamous band crash pad at 710 Ashbury in San Francisco.

Via extended archive footage, viewers join the Dead on its pilgrimage to the pyramids of Egypt, and go scuba diving with a bloated Garcia on the reefs off Kauai. They’re among the most poetic and touching moments in the film.

Fully titled “The Other One: The Long Strange Trip of Bob Weir,” the documentary seemingly exposes what the musician wants exposed. The bio’s glaring omission is Weir’s 2013 sloppy collapse onstage with Further in New York, a headline-making event that goes unexplained and unaddressed — as does the sudden cancellations of a series of his own band’s gigs not long after. This film’s Weir is thoughtful, relatively moderate and a master of his instrument.

Musicians influenced by the Dead line up to hail Weir’s work as second guitarist to Garcia. “I don’t know anybody who plays the guitar the way he does,” Garcia says in an archival interview. Weir says he focused on becoming more than the stereotypical rock rhythm guitarist by studying key jazz artists, particularly pianist McCoy Tyner in his support of John Coltrane. (This in a band sometimes derided as being the most successful amateur musicians of all time.)

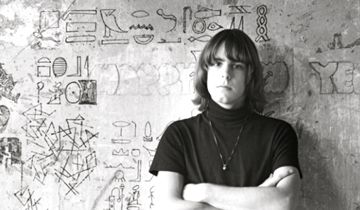

Garcia’s widow says Weir was “the magic object” at the center of the band. Many women agreed, with the boyish “heartthrob” of the Dead celebrated for his ability to pull groupies for himself and for the more savory characters in the band.

The self-described rock “tomcat” finally settled down, and his wife and children get welcome roles in the documentary, as does his sister and biological father.

Family — real and created — looms large in the story of the man who was adopted as an infant. “Jerry was my older brother, basically,” says Weir, who left home early to join up with the guitarist in a band called the Warlocks.

“I had to have the music, and so I went after it,” Weir says.

Another key male figure in Weir’s life was the beat generation icon Neal Cassady, whom the guitarist met as part of the Merry Pranksters.

Cassady stars in the song “The Other One,” which Weir says was the first number he wrote. Cassady died in Mexico the same night Weir was writing the Dead favorite, Weir says, repeating his old story about the dying man psychically reaching out to the musician.

Weir dismisses the Dead’s recorded output before 1970 as pretty rough, hangovers from the days of Acid Test jamming. The documentary presents the Dead’s music as getting its start with the early ’70s releases of “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty” — brushing past psychedelic classics such as “Anthem of the Sun” and “Aoxomoxoa.”

Also getting short shrift are the Dead’s key collaborators over the years, notably Robert Hunter, Tom Constanten, Brent Mydland, the Godchauxs and even Owsley Stanley.

Weir says he first noticed the Dead cultural phenomenon when the band started seeing the same faces in the front row nightly while on tour.

He exhibits mixed emotions about the fans who put their lives on hold to follow the band. Weir cites the burdens of celebrity. “Being famous is boring, and it’s confining,” he says.

He blames Garcia’s heroin habit partly on the fact that he couldn’t walk down a street due to the fame that engulfed the band figurehead in the 1980s.

Musical highlights include a performance of “Cassidy” with the National and a closing acoustic duet of the title song with bassist Dave Schools.

As streamed by Netflix, the film offers decent sonics and a tasteful surround soundstage. It runs 85 minutes. Director Fleiss’ credits include “God Bless Ozzy Osbourne,” although he’s better known as a producer (TV’s “The Bachelor”).

Netflix bought the Weir documentary during its film festival premieres.